symbicort asthma management plan symbicort inhaler uk igliving.com

From Aga Khan University, Karachi, Pakistan1; Sindh Medical College,

Dow University of Health Sciences, Karachi, Pakistan2; Penn State Hershey

Medical Center, Hershey, PA, USA3; Civil Hospital Karachi, Karachi, Pakistan4.

Corresponding Author:

Dr. Muhammad Bilal Abid

Email: mbilal.abid@gmail.com

Abstract

We report a case of lateral medullary syndrome (LMS) presenting with the sole symptom of dysphagia. Dysphagia is a fairly common symptom of LMS but to our knowledge, dysphagia presenting as the only presenting symptom for a brainstem infarction is rare. This type of clinical presentation can mimic quite a diverse variety of upper gastrointestinal tract and otorhinolaryngological pathologies, leading to unnecessary diagnostic workup. This case highlights the importance of keeping a high index of suspicion for central causes of dysphagia, specifically in the absence of other localizing signs and symptoms.

|

6go6ckt5b8|3000F7576AC3|Tab_Articles|Fulltext|0xf1ff2410020000001e01000001000900 6go6ckt5b5idvals|163 6go6ckt5b5idcol1|ID 6go6ckt5b5|2000F757Tab_Articles|Fulltext Introduction

Brainstem infarctions usually present with vivid constellation of signs and symptoms. But in rare situations, as in this case, they may also present with minimal clinical signs which may pose a diagnostic dilemma to clinicians at the time of initial presentation. Localized medullary infraction which presents with sole symptom of dysphagia may mimic a wide variety of diseases.

Case Report

A 60 year old, left-handed obese male, with hypertension, hyperlipidemia, coronary artery disease and diabetes mellitus, presented with solitary complaint of difficulty in swallowing. There was no associated fever, sore throat, cough, rhinorrhea, post-nasal drip or any other symptom suggestive of an upper respiratory tract infection. His dysphagia was acute in onset, moderate in severity and was not associated with food intake. He denied any recent sick contacts, hospital admissions or travel outside of his hometown. He did report a certain degree of burning sensation in his left nostril. At the time of presentation, he also denied any associated headache, visual changes, paraesthesia, weakness, numbness, incontinence or any other neurologic complaints.

On physical examination, the patient was afebrile and hemodynamically stable. Neurologic examination was unremarkable except for left side of face being hypersensitive. Later, during the course of hospital stay, he developed left-sided ptosis, mildly impaired peripheral vision of the left visual field, temperature and pain sensation hypersensitivity over the left side of face in comparison with the right side. The patient further went on to develop decreased pain and temperature sensation along the right side of his body, with slight dysmetria and hemiataxia on the left side.

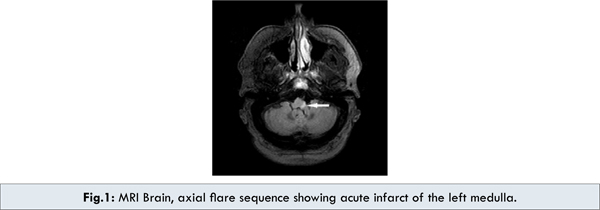

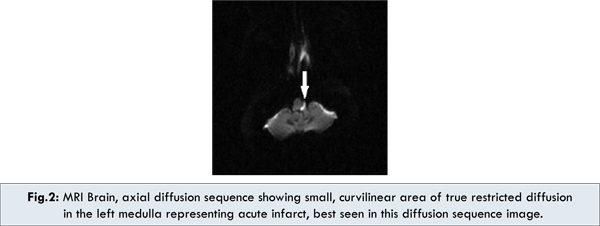

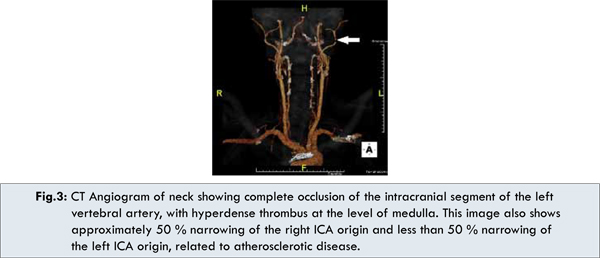

He was worked up for upper gastrointestinal tract and otorhinolaryngological causes of obstruction as a probable source of dysphagia. His CECT neck did not reveal any abnormality. Swallowing study revealed an abnormal swallowing reflex with weakness of the left pharynx, preferential passage of barium on the right side, and pooling in the left pyriform sinus with frank aspiration. MRI brain showed an infarct of the left medulla [Fig.1,2]. MRA confirmed occlusion of distal segments of the left vertebral artery. CT angiogram also confirmed the finding and showed a 50 % narrowing of both internal carotid artery origins [Fig.3]. EKG, cardiac enzymes and an echocardiogram were normal.

Aspirin, ACE inhibitors and statin were started and his blood sugar and blood pressure were controlled. Patient was discharged with a Keofeed in place for significant residual pharyngeal paralysis. He was scheduled for rehabilitation/physical therapy for electrical stimulation of the paralyzed region. One month later, he underwent a repeat swallow study which showed definite improvement in his swallowing function. He has been following up with his primary care physician and has done well in the slow wean off from Keofeeds.

Discussion

Lateral medullary infarction (LMI) or Wallenberg’s syndrome is one of the better known vascular syndromes of the posterior circulation [1,2]. The usual symptoms include vertigo, dizziness, nystagmus, ataxia, nausea and vomiting, dysphagia, hoarseness, impairment of pain and thermal sensation over the contralateral side, ipsilateral face and Horner’s syndrome [3,4]. As evident here, quite a few symptoms overlap with other organ systems of the body. Therefore, this syndrome can potentially mimic a diverse variety of medical conditions if a high index of suspicion is not maintained for a central cause. The dilemma of clinical indication towards diagnosis is further convoluted if LMI presents with solitary symptom of dysphagia, as in this patient. This can potentially lead physicians astray and result in extensive work up in the direction of ruling out other causes of dysphagia.

Although not the most frequently occurring, dysphagia has been reported in the medical literature as one of the more common symptoms of LMI, typically as part of a constellation of related symptoms, in the range of 23%-61% [5]. Several studies, conducted to delineate the clinical-radiologic correlation of medullary infarctions, reveal that dysphagia and palatopharyngeal dysfunction is the result of vascular compromise to the rostral part of ambiguous nucleus located in the dorsal component of the medulla oblongata. The rostro-caudal difference in the frequency of dysphagia seems to be explained by the anatomic characterization and has been validated by multiple topographic studies [6,7]. Dysphagia being the sole symptom of infarction is consistent with the observation that the stroke appears to have evolved from a much localized lesion in the rostral part of medulla, as the caudal part of medulla is not directly related to pharyngeal muscles [8,9]. Angiographic findings were consistent with vertebral artery disease, which more likely started as a small vessel infarction and evolved to involve a larger vascular territory. Risk factors in this patient were most likely his chronic non-communicable diseases including diabetes, hyperlipidemia, hypertension and obesity.

Aspirin, ACE inhibitors and statin were started and his blood sugar and blood pressure were controlled. Patient was discharged with a Keofeed in place for significant residual pharyngeal paralysis. He was scheduled for rehabilitation/physical therapy for electrical stimulation of the paralyzed region. One month later, he underwent a repeat swallow study which showed definite improvement in his swallowing function. He has been following up with his primary care physician and has done well in the slow wean off from Keofeeds.

Discussion

Lateral medullary infarction (LMI) or Wallenberg’s syndrome is one of the better known vascular syndromes of the posterior circulation [1,2]. The usual symptoms include vertigo, dizziness, nystagmus, ataxia, nausea and vomiting, dysphagia, hoarseness, impairment of pain and thermal sensation over the contralateral side, ipsilateral face and Horner’s syndrome [3,4]. As evident here, quite a few symptoms overlap with other organ systems of the body. Therefore, this syndrome can potentially mimic a diverse variety of medical conditions if a high index of suspicion is not maintained for a central cause. The dilemma of clinical indication towards diagnosis is further convoluted if LMI presents with solitary symptom of dysphagia, as in this patient. This can potentially lead physicians astray and result in extensive work up in the direction of ruling out other causes of dysphagia.

Although not the most frequently occurring, dysphagia has been reported in the medical literature as one of the more common symptoms of LMI, typically as part of a constellation of related symptoms, in the range of 23%-61% [5]. Several studies, conducted to delineate the clinical-radiologic correlation of medullary infarctions, reveal that dysphagia and palatopharyngeal dysfunction is the result of vascular compromise to the rostral part of ambiguous nucleus located in the dorsal component of the medulla oblongata. The rostro-caudal difference in the frequency of dysphagia seems to be explained by the anatomic characterization and has been validated by multiple topographic studies [6,7]. Dysphagia being the sole symptom of infarction is consistent with the observation that the stroke appears to have evolved from a much localized lesion in the rostral part of medulla, as the caudal part of medulla is not directly related to pharyngeal muscles [8,9]. Angiographic findings were consistent with vertebral artery disease, which more likely started as a small vessel infarction and evolved to involve a larger vascular territory. Risk factors in this patient were most likely his chronic non-communicable diseases including diabetes, hyperlipidemia, hypertension and obesity.

Treatment of established LMI includes symptomatic management with stabilization of neurologic status via anti-platelet therapy, control of blood sugar and blood pressure and feeding support in patients with dysphagia and risk of aspiration [10]. Long-term treatment mainly includes rehabilitation and physical therapy [11]. Several options are available for this purpose, including pharyngeal exercises, electrical stimulation and newer rTMS (repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation) [12]. Regarding prognosis, patients with large, rostral lesions tend to have severe dysphagia, aspiration pneumonia and prolonged admission. Nevertheless, our patient had a rather short hospital stay and fairly unremarkable transition into pharyngeal rehabilitation.

Conclusion

Although the most frequently occurring, ‘neurogenic dysphagia’ as a subset of oropharyngeal dysphagia represents a clinical entity worthy to be kept in mind as clinicians are confronted with the symptom of troubled swallowing, specifically in diabetic and hypertensive elderly.

Consent

Informed consent was taken from the patient to publish the information.

References

- Caplan LR. Posterior circulation disease: clinical findings, diagnosis, and management. Cambridge (MA): Blackwell Science. 1996:262-323.

- Savitz SI, Caplan LE. Vertebrobasilar disease. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2618.

- Park MH, Kim BJ, Koh SB, Park MK, Park KW, Lee DH. Lesional location of lateral medullary infarction presenting hiccups (singultus). J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76:95-98.

- Kim JS, Lee JH, Suh DC, Lee MC. Spectrum of lateral medullary syndrome. Correlation between clinical findings and magnetic resonance imaging in 33 subjects. Stroke. 1994;25:2298-2299.

- Kim JS. Pure lateral medullary infarction: clinical-radiologic correlation of 130 acute, consecutive patients. Brain. 2003;126:1864-1872.

- Kim H, Chung C-S, Lee K-H, Robbins J. Aspiration subsequent to a pure medullary infarction. Arch Neurol. 2000;57:478-483.

- Sacco RL, Freddo L, Bello JA, Odel JG, Onesti ST, Mohr JP. Wallenberg’s lateral medullary syndrome: clinical-magnetic resonance imaging correlation. Arch Neurol. 1993;50:609-614.

- Miller A. Neurophysiological basis of swallowing. Dysphagia. 1986;1:91-100.

- Nilsson H, Ekberg O, Sjoberg S, Olsson R. Pharyngeal constrictor paresis: an indication of neurologic disease? Dysphagia. 1993;8:239-243.

- Aichner F, Adelwohrer C, Haring HP. Rehabilitation approaches to stroke. J Neural Transm Suppl. 2002;63:59-73.

- Defanti CA, Tiraboschi P, Erli LC, Brambilla A, Felice B. Atypical features and prognosis of Wallenberg syndrome: longitudinal study. Ital J Neuro Sci. 1988;9:547-550.

- Chang WH, Kim YH, Bang OY, Kim ST, Park YH, Lee PK. Long-term effects of rTMS on motor recovery in patients after subacute stroke. J Rehabil Med. 2010;42:758-764.

|