6go6ckt5b8|3000F7576AC3|Tab_Articles|Fulltext|0xf1fff817020000001301000001000600

6go6ckt5b5idvals|165

6go6ckt5b5idcol1|ID

6go6ckt5b5|2000F757Tab_Articles|Fulltext

Introduction

The intraosseous lipoma constitutes approximately 0.1% of bone tumors [1]. It mostly occurs in lower limbs (71%) - particularly os-calcis (32%), femur (20%) and fibula (6%) [2]. Occurrence of lipoma in distal tibia is a rare entity in literature. Radiographically, it mimics nonossifying fibroma, simple cyst, aneurysmal bone cyst, fibrous dysplasia, giant-cell tumor, bone infarcts and chondroid tumor [2,3]. Because of being a radiographic illusion, the diagnosis is confirmed through histopathological examination [2]. We herein report a case of rare localization of intraosseous lipoma of distal tibia. We also discussed our preferred method of treatment in this case and its outcome.

Case Report

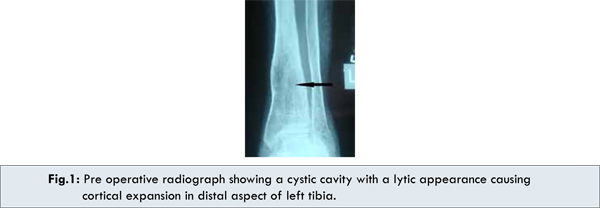

A 38-year-old female patient presented with pain in the left leg for past one year. Her pain had intensified in the last six months, particularly during performance of activities. There was no history of trauma or pain in any other part of body. Examination revealed bulbous, fusiform swelling of 5×5 cm in size at left distal tibia. She was walking with a limp, but had a normal range of motion at ankle and knee joints. The distal part of left tibia was sensitive to deep palpation. Rest of her general physical and systemic examination was unremarkable. Her whole bloodcount and routine blood tests, including the sedimentation and CRP, were normal. Roentgenogram revealed a wide cystic cavity with a lytic appearance causing cortical expansion in distal aspect of left tibia without involvement of ankle joint [Fig.1].

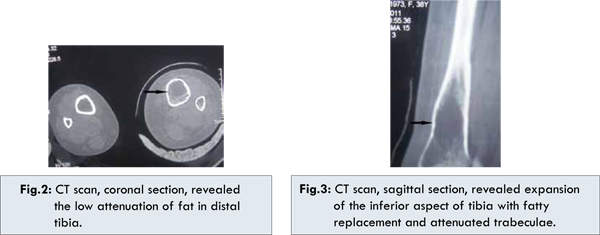

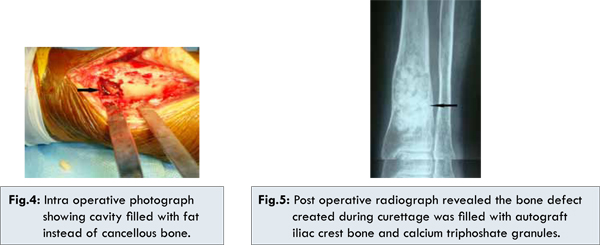

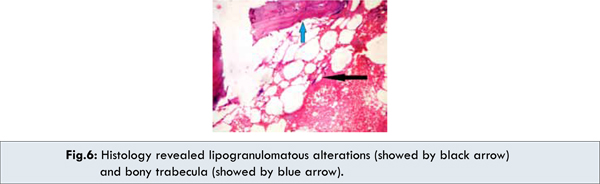

Leg CT scan was obtained, which revealed expansion of the inferior aspect of tibia with fatty replacement and attenuated trabeculae. Tibial plafond and ankle joint appears to be normal [Fig.2,3]. Open biopsy was planned for differential diagnosis. Through an anterolateral approach to tibia, tumor site was exposed. A bone window was created in the lateral cortex [Fig.4]. The mass was taken out through extended curettage. The cavity was very large and no cancellous bone was present. The curetted material was sent for histopathology examination. Subsequently,the bone defect created during curettage was filled with autograft iliac crest bone and calcium triphoshate granules [Fig.5]. The detailed histopathological examination of the extracted materials revealed lipogranulomatous alterations and thin trabecular lamella, which were reported as mature adipose tissue-intraosseouslipoma scattered throughout the bone [Fig.6].

The patient’s postoperative course was uneventful. She was mobilized on the third day without bearing weight. She was followed up by X-rays, and full weight-bearing was allowed at the end of third month upon consolidation of the graft tissue.

Discussion

Intraosseus lipoma was first described in 1880 [4]. The largest reported series was of sixty six cases by Milgram [3]. Campbell et al conducted a metanalysis of total of 206 cases, including those in Milgram’s study [2]. Patients are in age from 5 to 85 years, with the lesions most frequently being discovered in the 4th and 5th decades of life [5]. Intraosseous lipomas have been reported to occur in equal frequency in both genders [6].

Patients are frequently asymptomatic and their lesions are discovered incidentally. Seventy percent of symptomatic patients present with pain. Some may present with swelling or even a pathological fracture [2,7]. Microtrabecular fractures occurring subsequent to minor trauma in the weakened bone have been blamed for the pain. However, pathological fractures are extremely rare in these tumors [2]. Our case presented with both pain and swelling.

Milgram has proposed 3 stages of intraoseouslipoma [3,8]. Stage 1 consists of radiolucent expansile lesion, viable lipocytes on histological examination, and some fine bone trabeculae. Stage 2 lesions are radiologically similar to stage 1 lesion, but they exhibit partial fat necrosis and focal calcification with regions of viable lipocytes. Stage 3 shows complete fat necrosis during histological examination. Radiologically it shows a reactive ossified rim, some central cysts and calcification. Therefore, each stage shows radiological features that can be correlated with the histological findings [9]. Our case was consistent with grade 1 of Milgram staging.

The intraosseous lipoma has nonspecific appearance and shares the same features of nonossifying fibroma, simple cyst, aneurysmal bone cyst, fibrous dysplasia, giant-cell tumor, bone infarcts and chondroid tumor [2,3]. Intraosseous lipoma contains only fat and thus is easily differentiated from other primary osseous lesions at Magnetic resonance Imaging (MRI) or Computerized Tomography (CT) because both modalities offer the ability to document the intrinsic lesional adipose tissue [5]. Computerized Tomography demonstrates the low attenuation of fat (<–60 to –100 HU) and MRI shows T1 prolongation and T2 shortening similar to subcutaneous fat [5,6]. We performed CT scan in our patient to differentiate it from other primary bone lesions. The lesion displayed the fat attenuation without a soft tissue component.

Secondary malignancies are very rare in intraosseous lipomas. Milgram [10] reported 4 cases of presumed malignant transformation of intraosseous lipoma (one in stage 1 and three in stage 3 of Milgram staging) into malignant fibrous histiocytoma or liposarcoma. The risk factors, sex predilection were not addressed in the literature. So, one must be cautious. Our patient is in our regular follow up and has shown no evidence of malignancy or recurrence.

The need for surgical treatment is controversial. Curettage with bone grafting is the treatment of choice when surgical intervention is needed. Most intraosseous lipomas, however, can be managed conservatively. Some surgeons feel that in asymptomatic cases with no signs of an impending pathologic fracture or suspicion of malignancy, nonoperative treatment with clinical and radiological follow-up is a wise approach [3].

In conclusion, the orthopedic surgeon should consider intraosseous lipoma in the differential diagnosis of lytic lesions of long bones. In cases with a high risk of fracture, curettage and bone grafting is a good option for treatment with an excellent clinical and functional result.

References

- Unni KK. Lipoma and liposarcoma. In Dahlin’s bone tumors. General aspect and data on 11,087 cases. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven:1996;349-352.

- Campbell RS, Grainger AJ, Mangham DC, Beggs I, Teh J, Davies AM. Intraosseous lipoma: report of 35 new cases and a review of the literature. Skeletal Radiol. 2003;32:209-222.

- Milgram JW. Intraosseous lipomas. A clinico pathologic study of 66 cases. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1988;231:277-302.

- Reigh BV, Guinot TJ, Risent MF, Aparisi RF, Ferrer JR. Computed tomography of Intraosseous lipoma of oscalcis. Clin Orthop 1987;221:286-291.

- Murphey MD, Carroll JF, Flemming DJ, Pope TL, Gannon FH, Kransdorf MJ. Benign Musculoskeletal Lipomatous Lesions. RadioGraphics. 2004;24:1433-1466.

- Levin MF, Vellet AD, Munk PL, McLean CA. Intraosseous lipoma of the distal femur: MRI appearance. Skeletal Radiol. 1996;25:82-84.

- Mueller MC, Robbins JL. Intramedullary lipoma of bone. Report of a case. J Bone Joint Surg. 1960; 42A:517.

- Milgram JW. Intraosseous lipoma: radiologic and pathologic manifestation. Radiology. 1988;167:155-160.

- Lam FCY, Leung JLY, Shu SJ, Chan ACL, Chan MK, Fung DHS. Intraosseous lipoma : Report of 2 cases. J HK Coll Radiol. 2004;7:145-148.

- Milgram JW. Malignant transformation in bone lipoma. Skeletal Radiol. 1990;19:347-352.