6go6ckt5b8|3000F7576AC3|Tab_Articles|Fulltext|0xf1ff642f020000001e01000001000a00

6go6ckt5b5idvals|171

6go6ckt5b5idcol1|ID

6go6ckt5b5|2000F757Tab_Articles|Fulltext

Introduction

Although an uncommon neoplasm, Desmoid tumor (aka Aggressive Fibromatosis) is still the most common primary malignancy of the abdominal wall and mesentery. Mesenteric and intra-abdominal desmoids, although commonly seen in patients with Familial Adenomatous Polyposis (FAP), especially with Gardner’s syndrome, do occur sporadically [1]. Contiguous, local infiltration of surrounding organs such as small bowel, ureters and aorta, accounts for the morbidity and mortality seen with this condition.

While the treatment of desmoid tumors is still controversial, it is generally agreed upon that symptomatic patients should undergo surgery with an attempt at complete resection to achieve negative margins [2]. Newer treatment modalities such as radiation therapy and chemotherapy are generally reserved for unresectable, clinically aggressive tumors [3].

Case Report

A 45-year-old female, underwent a right ovarian cystectomy for ovarian endometriosis via a right lower paramedian incision. Following surgery, the patient was doing well with improvement in the symptoms of dysmenorrhea. Three years post surgery, the patient developed an area of irregular scar-like induration with variegated pigmentation and ulceration in the lower aspect of the previous right lower paramedian incision [Fig.1]. The mass was firm to hard in consistency, measuring 15 × 13 cm and was seen to arise from the parietes as evidenced by the leg raising test. Hematological and biochemical parameters were essentially normal except for the presence of eosinophilia and an elevated ESR. An incision biopsy was taken from the abdominal mass and ulcer edge which revealed chronic non-specific inflammation.

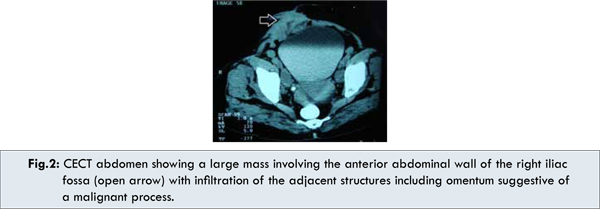

A CECT scan of the whole abdomen showed a large mass involving the anterior abdominal wall of the right iliac fossa region without evidence of cystic degeneration or abscess formation. The mass was seen to infiltrate the adjacent structures including the omentum, suggestive of a malignant process [Fig.2]. Also, there was presence of right-sided hydroureter with hydronephrosis, possibly due to extrinsic compression of the right lower ureter. In addition, a colonoscopy was performed which failed to reveal colorectal polyps. With these findings, a provisional diagnosis of abdominal desmoid was made and the patient went under the knife. Intra-operatively, the parietal mass was seen to involve the right rectus abdominis muscle, the greater omentum, the uterus and the right adnexa. These structures were therefore sequentially removed [Fig.3a]. The right lower ureter was seen to be encased by the mass and accordingly a segmental resection of the ureter was done with ureteric reimplantation. The resulting defect in the anterior abdominal wall was repaired using a synthetic fabric patch (G-patch®) and prolene mesh followed by an abdominoplasty [Fig.3b].

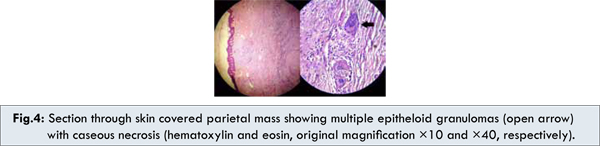

Post-operatively, the patient showed good recovery without undue complications other than a seroma of the incision wound which resolved with regular dressings. However, histopathology report showed the presence of multiple epithelioid granulomas with caseous necrosis in the endomyometrium, ovary, fallopian tubes, parietal mass and omental tissue with the diagnosis of tuberculosis [Fig. 4a, 4b]. The patient was started on anti- tubercular drugs and is doing well.

Discussion

From the discussion on desmoid tumors, it is quite evident that the case in question bears an undeniable resemblance with abdominal desmoid tumors viz. the occurrence in a middle aged women of an enlarging, painless thickening of the infra-umbilical wall following abdominal surgery. Notably absent where the constitutional symptoms associated with tuberculosis. The CT scan further reinforced our suspicion, showing a large parietal mass with infiltration of intra-abdominal structures. Although a histological diagnosis could not be established, the clinical findings and the radiological features strongly favored desmoid as the primary diagnostic consideration [4].

Albeit, the recurrence rate following surgical excision of abdominal wall and intra-abdominal desmoids may be as high as 40% and 60-85%, respectively [5], a decision to operate was undertaken based on objective evidence of right sided obstructive uropathy and cosmetic concerns expressed by the patient. Intra operatively, the involvement of the right adnexa and uterus prompted their removal as well. At this point of time, our interest lay in the extensiveness of the desmoid tumor and even though there were reports of multicentric desmoids involving the abdominal wall and mesentery, and even one of contiguous involvement of the abdominal wall by a mesenteric desmoid, such cases were distinctly rare [6].

Our interest in the case, however, took a U-turn following the histopathology report of the resected specimen. Abdominal tuberculosis can involve any intra- abdominal structure, most notably the peritoneum and the omentum [7]. There are also many reports in the literature on pelvic tuberculosis, involving the uterus and adnexa (esp. the fallopian tubes, which are almost always involved) [8]. This, we presume may have been responsible for the patient’s earlier symptoms of dysmenorrhea for which she underwent surgery with a presumptive diagnosis of ovarian endometriosis.

Conclusion

Tuberculosis continues to be a major cause of morbidity and mortality especially in the developing world. Its incidence is rising worldwide as a result of occurrence of multidrug resistant strains and the increasing incidence of HIV-AIDS [9]. This experience goes to demonstrate the seemingly endless forms and presentations of this ancient disease. It would appear that just as all organisms must continually evolve to ensure their survival, so too has this enduring foe. As the worldwide incidence and awareness of cancer increases, there is an inclination on the part of the treating doctor to regard malignancies in the top of their differential diagnosis list (the ‘presume to be cancer unless otherwise proven’ strategy). While this approach may be justifiable, it can, at times, prove to be a double edged sword.

Therefore, it is imperative that we as clinicians of the modern era, while embracing the new, must keep an eye on the old because where, when and how this old master will strike next – who knows.

References

- Bruce JM, Bradley EL 3rd, Satchidanand SK. A desmoid tumor of the pancreas: Sporadic intraabdominal desmoids revisited. Int J Pancreatol. 1996;19:197-203.

- Merchant NB, Lewis JJ, Woodruff JM, Leung DH, Brennan MF. Extremity and trunk desmoid tumors: a multifactorial analysis of outcome. Cancer. 1999;86:2045–2052.

- Okuno SH, Edmonson JH. Combination chemotherapy for desmoid tumors. Cancer. 2003;97:1134–1135.

- Casillas J, Sais GJ, Greve JL, Iparraguirre MC, Morillo G. Imaging of intra- and extra-abdominal desmoid tumors. RadioGraphics. 1991;11:959–968.

- Biermann JS. Desmoid tumors. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2000;1:262-266.

- Schweitzer RJ, Robbins GF. A Desmoid Tumor of Multicentric Origin. AMA Arch Surg. 1960;80:489-494.

- Sunil Kumar et al. Abdominal tuberculosis. In: Johnson CD, Taylor I, editors. Recent Advances in Surgery, Vol. 28, London: Royal Society of Medicine Press; 2005. pp.49.

- Chavhan GB, Hira P, Rathod K, Zacharia TT, Chawala A, Badhe P et al. Female genital tuberculosis: hysterosalpingographic appearances. Br J Radiol. 2004; 77:164-169

- Sheer TA, Coyle WJ. Gastrointestinal tuberculosis. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2003;5:273-278.