Ashok Kumar Parida, Moushumi Lodh1, Joy Sanyal, Vikas Sharma2, Indranil Dev,

Arunangshu Ganguly

From the Department of Cardiology, Biochemistry1 and Radiology2,

The Mission Hospital, Durgapur, West Bengal, India.

Corresponding Author:

Dr. Moushumi Lodh

Email: drmoushumilodh@gmail.com

Abstract

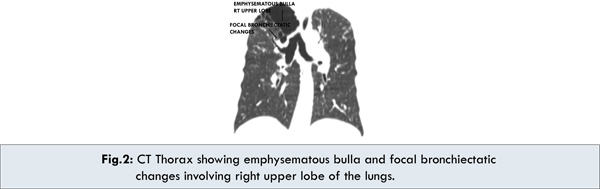

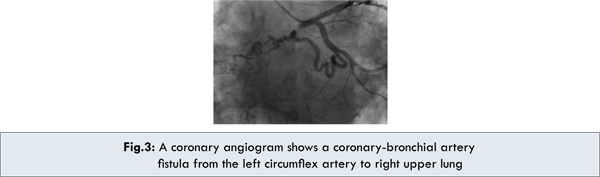

Background: Most patients with coronary-bronchial fistulas are asymptomatic. However, some patients present with congestive heart failure, infective endocarditis, myocardial ischemia induced by a coronary steal phenomenon, or rupture of an aneurysmal fistula. Our case of coronary-bronchial steal presented with massive hemoptysis and anginal pain. Methods: CT scan chest showed an emphysematous bulla and focal bronchiectatic changes involving right upper lobe. Coronary angiography revealed a large fistula connecting left circumflex coronary artery to right bronchial artery. A covered stent was placed in proximal left circumflex artery and collaterals excluded. Result: His angina resolved and dyspnea improved. Hemoptysis reduced from about 500 ml per day to about 50 ml a day, in ten days. 6-month follow-up has been uneventful without recurrence of angina or hemoptysis. Conclusion: This report highlights the importance coronary angiography in detecting coronary artery abnormalities in patients with hemoptysis. Although previously treated with surgical ligation, interventional therapies are justifiably becoming more widely used to correct vascular insufficiencies.

|

6go6ckt5b8|3000F7576AC3|Tab_Articles|Fulltext|0xf1ff043f020000009b01000001000600 6go6ckt5b5idvals|173 6go6ckt5b5idcol1|ID 6go6ckt5b5|2000F757Tab_Articles|Fulltext Introduction

Coronary to bronchial artery fistula [CBF] is present at birth and remains closed and asymptomatic in most of the population. However, this anastomosis may become enlarged and functional in various cardiovascular and chronic pulmonary diseases with an incidence of about 0.6% [1]. In severe or intractable hemoptysis, it is a common practice to do bronchial artery angiogram to detect the culprit artery and embolize them to prevent further bleeding. Here the bronchial artery angiogram proved negative. So the challenge for us lay in pinpointing CBF as the cause of severe hemoptysis with angina symptoms and treating it in time so as to avoid fatal consequences of hemoptysis. The presence of associated chest pain and effort breathlessness, were pointers to rule out ischaemic heart disease.

Case Report

A 75 year old O positive male patient, complaining of intermittent chest pain since last 1 week, more frequent and aggravated for the last 3 days and associated with massive hemoptysis, sweating shortness of breath and syncope was admitted from the emergency department. He complained of fever since 15 days which subsided with antipyretics and was associated with cough and expectoration. He was known to have hypertension. At presentation, his blood pressure was 90/60 mm Hg, pulse 102 /min, respiratory rate 30 breaths/min, crepitation’s were present over right infraclavicular area. S1, S2 were audible and regular. All peripheral pulses were palpable. He was alert and conscious. The patient did not have pallor, jaundice, cyanosis, clubbing or edema. Abdomen was soft, non-tender and there was no organomegaly. Peristaltic sounds were audible. The laboratory test results were within normal limits except the CRP 19.5 mg/L [<6 mg/L], CKMass and troponin I were within reference range. Lipid profile was as follows: total cholesterol 212 [<200 mg/dl], triglyceride 178 [<150 mg/dl], LDL Cholesterol 108 [<100 mg/dl] and HDL cholesterol 30 [>40 mg/dl].

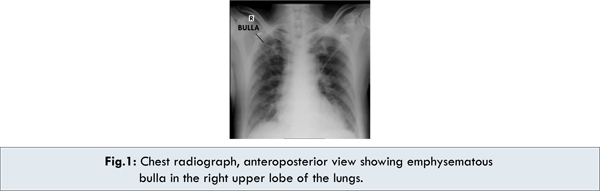

Chest X ray showed bronchiectatic lung cavity in right upper lobe [Fig.1]. Chest CT showed emphysematous bulla and focal bronchiectatic changes involving right upper lobe [Fig.2]. ECG showed left bundle branch block pattern, ECHO showed normal left ventricular systolic function, sclerotic aortic valve left ventricular ejection fraction was 67 % with grade 1 diastolic dysfunction.

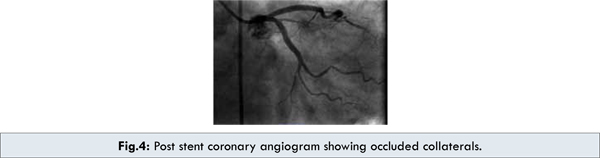

Based on this, a working diagnosis of bronchiectasis with unstable angina was made. Due to presence of left bundle branch block, and chest pain, a TMT was not considered for evaluation of ischaemic heart disease. Aortogram and selective bronchial artery angiogram did not reveal any culprit vessel for hemoptysis. A coronary angiography was performed to find a cause for the chest pain. Coronary angiography revealed right dominant coronaries. However, largeanomalous collateral was present connecting the proximal left circumflex artery to the right bronchial artery [Fig.3]. Some extravasation of dye was noted in the right upper zone. In view of the poor general condition of the patient, surgical intervention was ruled out. Treatments considered included coil embolization, PVA bead embolization and covered stent to exclude the collateral. Since the artery connecting to the bronchial artery originated from the junction of proximal and distal part of left circumflex artery, hooking the ostium entailed traversing of catheter through the main large circumflex artery proximal part, the possibility of injuring the coronary artery would have been very high. So, placing a covered stent across the origin of the fistula with care to cover adequately the part proximal and distal to the fistula [so as to prevent endoleak] was planned. A covered stent was placed in the proximal left circumflex artery and collateral artery was excluded using Prograft [3.5x15] balloon expandable covered stent [Fig.4].

His angina resolved and dyspnea and hemoptysis reduced. He was discharged from the hospital after ten days. At a 6-month follow-up, he was asymptomatic. Follow-up echocardiography shows no regional wall motion abnormalities. A follow-up angiogram was obtained. There was no restenosis at the stented site and no recanalization.

Discussion

A Coronary bronchial artery fistula [CBF] is detected in 0.18% of patients who undergo routine coronary angiography [2]. When the coronary fistula drains into the right side of the heart, the volume load is increased to the right heart as well as to the pulmonary vascular bed, the left atrium, and left ventricle.When the fistula drains into the left atrium or the left ventricle, there is volume overloading of these chambers but no increase in the pulmonary blood flow. This results in varied appearance of dilation of different cardiac chambers due to the shunts on echocardiography. The size of the shunt is determined by the size of the fistula and the pressure difference between the coronary artery and the chamber into which the fistula drains.

Most patients are asymptomatic. Chest pain is the most common presenting symptom in about 52% cases and dyspnea in 24% cases of coronary fistulas [3]. When symptomatic, the most common findings are heart failure secondary to volume overload resulting from left to right shunting, ischemia secondary to coronary steal, arrhythmia, fistula rupture or thrombosis, and infective endocarditis [4]. The severity of clinical features of a CBF depends on the degree of the left-to-right shunt and hemoptysis. As the degree of the left-to-right shunt increases, complications such as pulmonary hypertension or congestive heart failure occur more frequently. The most common origin for coronary fistulas is from the left anterior descending artery (LAD), followed by the right coronary artery (RCA) and circumflex artery and drainage is most commonly into pulmonary artery [3].

Several previous reports [2] have proposed that patients with a coronary-bronchial artery fistula need aggressive treatment, including embolization, in order to prevent lethal complications such as aneurismal rupture or infective endocarditis. Some advocate closure of coronary artery fistulae even in asymptomatic patients [4].Shin et al [5] have proposed prophylactic and therapeutic embolization of coronary-bronchial artery fistula in patients with bronchiectasis. However, embolization, although less invasive, can be safely performed only after the anatomical relationships between the fistula and the surrounding structures are completely assessed.

Transcatheter closure is an emerging alternative in patients with suitable anatomy and those without other complex cardiac lesions such as concomitant valvular heart disease. First reported by Reidy in 1983 [6] overall, the results have been comparable to surgery with low morbidity and mortality. In fact, transcatheter closure has several theoretical advantages over open heart surgery, including shorter hospitalization and quicker recovery. The treated vessel after occlusion becomes thrombosed and the reduction in left to right shunt causes myocardial perfusion return to normal. However, a minority of patients treated with percutaneous transcatheter closure will experience recanalization. Routine clinical follow-up in all and imaging surveillance after closure in symptomatic patients should be considered after transcatheter coronary artery fistulae closure.

Conclusion

Catheter closure can also be performed with a variety of techniques, including detachable balloons, stainless steel coils, controlled-release coils, controlled release patent ductus arteriosus coils, patent ductus arteriosus plug, regular and covered stents, and various chemicals [7]. Our choice of a covered stent in this case was based on the finding of suitable anatomy wherein a single covered stent would safely exclude the collateral. Coil embolization was unlikely to be successful as the collateral was extremely tortuous proximally. Particle embolization was not done in view of coronary artery thrombosis.

References

- Yoon JY, Jeon EY, Lee IJ, Koh SH. Coronary to Bronchial Artery Fistula Causing Massive Hemoptysis in Patients with Longstanding Pulmonary Tuberculosis. Korean J Radiol. 2012;13:102-106.

- Lee WS, Lee SA, Chee HK, Hwang JJ, Park JB, Lee JH. Coronary-Bronchial Artery Fistula Manifested by Hemoptysis and Myocardial Ischemia in a Patient with Bronchiectasis. Korean J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;45:49-52.

- Jama A, Barsoum M, Bjarnason H, Holmes DR, Rihal CS. Percutaneous Closure of Congenital Coronary Artery Fistulae Results and Angiographic Follow-Up. J Am Coll Cardiol Intv. 2011;4:814–821.

- Tirilomis T, Aleksic I, Busch T, Zenker D, Ruschewski W, Dalichau H. Congenital coronary artery fistulas in adults: surgical treatment and outcome. Int J Cardiol. 2005;98:57–59.

- Shin KC, Shin MS, Park JW, Kang WC, Kim EJ, Lee KH et al. Prophylactic and therapeuticembolization of coronary-bronchial artery fistula inpatient with Bronchiectasis. Int J Cardiol. 2011;151:e71-e73.

- Reidy JF, Baker E, Tynan M. Transcatheter occlusion of a Blalock-Taussig shunt with a detachable balloon in a child. Br Heart J. 1983;50:101–103.

- Koneru J, Samuel A, Joshi M, Hamden A, Shamoon FE, Bikkina M. Coronary Anomaly and Coronary Artery Fistula as Cause of Angina Pectoris with Literature Review. Case Reports in Vascular Medicine. 2011; Article ID 486187, 5 pages doi:10.1155/2011/486187.

|