Chih-Cheng Wu, Huan Hsu, Chih-Jen Hung, Cheng-Ming Peng1, Yi-Wen Chang

From the Department of Anesthesiology and Department of General Surgery1; Taichung Veterans General Hospital; Xitun Dist.; Taichung City 407; Taiwan (R.O.C.).

Corresponding Author:

Dr. Yi-Wen Chang

Email: yvonne627@msn.com

Abstract

We report the novel use of a Sengstaken-Blakemore tube in an 82-year-old man with severe upper gastrointestinal bleeding and subsequent hypovolemic shock. When exploratory laparotomy failed to locate the source of the bleeding, a Sengstaken-Blakemore tube was placed retrograde to the gastroesophageal junction using a previously inserted nasogastric tube for guidance. The bleeding stopped immediately after mechanical compression by the inflated gastric and esophageal balloons. Hemodynamic stability permitted a thorough evaluation of the surgical field. The balloons were deflated intermittently to allow the surgeon to address the major and other smaller bleeding vessels in a stepwise manner. The intraoperative insertion of a Sengstaken-Blakemore tube can be used to control disastrous upper gastrointestinal bleeding located at or above the gastroesophagealjunction. It helps to achieve hemodynamic stability with less transfusion required and results in fewer complications. However, the lack of experience with the direct placement of a Sengstaken-Blakemore tube and the need for the equipment-dependent confirmation of the Sengstaken-Blakemore tube position reduces its clinical usage. The retrograde Sengstaken-Blakemore tube insertion strategy does not require assistance by ultrasonography or endoscopy and avoids most procedure-related complications.

|

6go6ckt5b8|3000F7576AC3|Tab_Articles|Fulltext|0xf1ff84fa02000000c601000001001200 6go6ckt5b5idvals|197 6go6ckt5b5idcol1|ID 6go6ckt5b5|2000F757Tab_Articles|Fulltext Introduction

Introduced in 1950, the Sengstaken-Blakemore (SB) tube was initially designed to provide mechanical tamponade by two inflatable balloons (one for the stomach and one for the esophagus) for uncontrolled esophageal/gastric variceal bleeding [1]. The SB tube is frequently used in the emergency room or on the ward by physicians but is rarely used intraoperatively. We describe the case of an elderly man with upper gastrointestinal (UGI) bleeding in whom balloon tamponade was achieved by the retrograde nasogastric-tube-guided insertion of the SB tube during an operation. This alternative method of insertion effectively stopped the bleeding. We believe this is the first time this method has been reported in the literature.

Case Report

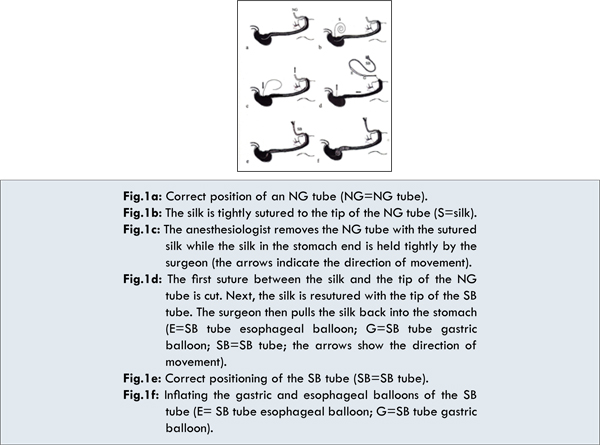

An 82-year-old man was diagnosed with adenocarcinoma involving the antrum of the stomach (Borrmann type 3; pT4aN3M0; stage IV) and a very low-risk gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) involving the body of the stomach. He underwent a subtotal gastrectomy, D2 lymph node dissection, and Billroth-II anastomosis. Three weeks later, he suffered from septic shock due to duodenal stump leakage and underwent a second operation including duodenostomy and gastrorrhaphy. The sudden onset of massive hematemesis occurred 40 days after surgery. A nasogastric (NG) tube was placed immediately to drain the stomach contents [Fig.1a], and endoscopic therapy was arranged but failed due to circulatory collapse caused by tremendous bleeding. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation and intragastric blood clot tamponade temporarily restored the patient’s vital signs, and an emergency operation was warranted to evaluate the bleeding.

Upon his arrival in the operation room, patient’s blood pressure was 80/50 mmHg with a pulse rate of 110/min. General anesthesia was induced, and two large-bore central lines with double-lumen 8 Fr and large-bore multi-lumen central venous catheterization (Arrow International, Reading, PA, USA) were inserted through the bilateral internal jugular veins. The preoperative hemoglobin level was 7.6 g/dL despite persistent aggressive volume expansion.

After opening the stomach, massive bleeding caused profound hypotension (systolic blood pressure below 50 mm Hg). A massive blood transfusion with more than 10 units of packed red blood cells and 12 units of fresh frozen plasma and the administration of a vasoactive agent [dopamine 5-7.5 mcg/kg/min and norepinephrine bitartrate (Levophed®; USA, 0.08-0.1 mcg/kg/min)] were in vain. Additionally, the outpouring blood in the stomach made identifying the location of bleeding extremely difficult.

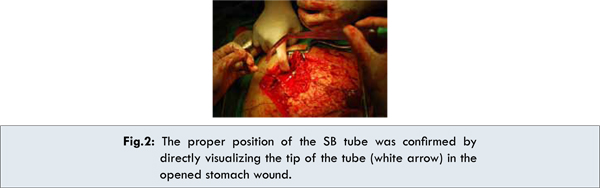

The anesthesiologist suggested placing an SB tube to stop the bleeding. The surgeon placed a silk suture at the end of the NG tube via the stomach wound [Fig.1b]. The NG tube was then pulled out through the patient’s nostril while the end of the silk suture in the stomach was held tightly by the surgeon [Fig.1c]. Above the nostril, the silk was cut and re-tied to the tip of an SB tube. The end of the silk suture in the stomach was then pulled back by the surgeon as a guide for the SB tube that was inserted through the nostril [Fig.1d]. After visually confirming the correct position [Fig.2], the gastric and esophageal balloons were inflated and supplied sufficient traction to compress the esophagus and the gastroesophageal junction [Fig.1f]. The bleeding decreased dramatically. With adequate volume resuscitation, the blood pressure stabilized within 5 minutes, and the patient’s systolic pressure rose to 110 mm Hg. With the surgical field then relatively clear, all additional bleeding sources could be identified. The balloons were deflated intermittently to allow the surgeon to tie or cauterize the major and other smaller bleeding vessels. The patient’s vital signs remained stable, and the vasoactive agents were gradually tapered. The SB tube was removed smoothly after completion of the surgery. The postoperative diagnosis was bleeding from multiple gastric and gastroesophageal junction ulcers after suture ligation.

The patient was transferred to the surgical intensive care unit after surgery, he regained consciousness and was weaned from the ventilator 5 days later. Unfortunately, the patient expired 2 months later due to the sixth refractory recurrent ulcer bleeding episode and septic shock despite an aggressive operation and medical management.

Discussion

The initial management of patients in hypovolemic shock with UGI bleeding requires resuscitation with volume expanders. Intravenous proton pump inhibitors or histamine-2 receptor antagonists should be initiated as the first-line treatment. Endoscopic therapy should then be considered. Surgery is indicated only when bleeding cannot be controlled endoscopically or complication like perforation is present [2].

The skills required to insert the SB tube include direct insertion or retrograde insertion. During direct insertion, technical problems may be encountered due to the larger tube size compared to an NG tube. It is even more difficult to insert the tube in a paralyzed patient with an endotracheal tube in place. The balloon of the endotracheal tube usually interferes with the passage of the tube through the esophagus. A previously inserted NG tube can be used to achieve a better retrograde procedure, particularly because most patients first receive NG tube irrigation when UGI bleeding is suspected.

Balloon tamponade is used less often because of the high incidence of complications (>15%), including accidental inflation of the gastric balloon in the esophagus, mediastinum, or bronchus [3], balloon malposition, aspiration pneumonitis, esophageal perforation, ulceration [4], and even transient bilateral parotitis [5]. The optimal position of an SB tube should be confirmed by a portable chest x-ray, although the gastric balloon is not always visible on radiographs [6]. Some researchers suggest using endoscopy or ultrasonography to confirm the location, but very specialized facilities and skill are required for this procedure [6-9]. Freezing the tube has also been suggested to help straighten it before insertion [9].

As in this case report, the tube can be placed in the proper position under guidance and visual confirmation without intervention requiring other special facilities during surgery. Using the silk suture as a guide, the risk of tissue trauma due to blind insertion of the SB tube through the nasal cavity, retropharyngeal space, and even esophageal wall can be reduced. The tube can be removed after the bleeding vessels are tied to avoid the risk of esophageal fistula formation and an uncomfortable “stretched” sensation for the patient after recovery from anesthesia. Other mechanical decompression tubes, such as the Linton-Nachlas tube or Minnesota tube, might be used in a similar manner.

Using an SB tube helps to apply effective mechanical compression over the bleeding points. Using intermittent pressure release, surgeons can use a stepwise management approach with a clearer view of the surgical field. The patient vital signs are also easier to maintain by the anesthesiologists, requiring fewer transfusions and less medication. This approach is also undoubtedly more cost-effective.

There are several limitations to this case report. The reported method requires good communication and cooperation between the anesthesiologists and the surgeons. The risk of peritonitis may also be increased due to repeated manipulation of the digestive tract. Furthermore, this method is only suitable for bleeding points located over the esophagus and gastroesophageal junction or cardiac regions of the stomach.

Conclusion

Massive UGI bleeding with unstable vital signs requires emergency treatment. Delays of any kind, including waiting for radiologic confirmation, increase the morbidity and mortality risk for these patients. Compared to conventional methods, the retrograde insertion of an SB tube is an easily learned, technically simple, more effective and more efficient method, with a lower incidence of complications. Greater use of this technique should be considered intraoperatively.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest whatsoever arising out of the publication of this manuscript.

References

- Sengstaken RW, Blakemore AH. Balloon tamponage for the control of hemorrhage from esophageal varices. Ann Surg. 1950;131:781-789.

- Wee E. Management of nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. J Postgrad Med. 2011;57:161-167.

- Lin CT, Huang TW, Lee SC, Kuo SM, Hsu KF, Hsu PS, et al. Sengstaken-Blakemore tube related esophageal rupture. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2010;102:395-396.

- Seet E, Beevee S, Cheng A, Lim E. The Sengstaken-Blakemore tube: uses and abuses. Singapore Med J. 2008;49: e195-e197.

- Tekin F, Ozutemiz O, Bicak S, Oruc N, Ilter T. Bilateral acute parotitis following insertion of a Sengstaken-Blakemore tube. Endoscopy. 2009;41 Suppl 2:E206.

- Lin AC, Hsu YH, Wang TL, Chong CF. Placement confirmation of Sengstaken-Blakemore tube by ultrasound. Emerg Med J. 2006;23:487.

- McCormick PA, Burroughs AK, McIntyre N. How to insert a Sengstaken-Blakemore tube. Br J Hosp Med. 1990;43:274-277.

- Lin TC, Bilir BM, Powis ME. Endoscopic placement of Sengstaken-Blakemore tube. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2000;31:29-32.

- Kaza CS, Rigas B. Rapid placement of the Sengstaken-Blakemore tube using a guidewire. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;34:282.

|