|

Ersin Gürkan Dumlu, Mesut Özdedeoglu, Birkan Bozkurt, Mehmet Tokaç, Samet Yalçin2, Mehmet Kiliç2

From the Department of General Surgery1, Ataturk Research and Training Hospital, Ankara 06800, Turkey; Department of General Surgery2, Yildirim Beyazit University, Ankara 06800, Turkey.

Corresponding Author:

Dr. Ersin Gurkan DUMLU

Email: gurkandumlu@gmail.com

Abstract

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) are the most common mesenchymal tumors of the gastrointestinal tract. Surgery is the primary choice for GIST treatment. However, there is no consensus on the best primary treatment for duodenal stromal tumors. In this study, we discuss the surgical treatment options for duodenal stromal tumors and the clinical outcomes of these treatments with this sample case.

|

6go6ckt5b8|3000F7576AC3|Tab_Articles|Fulltext|0xf1ffb46904000000d901000001000900 6go6ckt5b5idvals|257 6go6ckt5b5idcol1|ID 6go6ckt5b5|2000F757Tab_Articles|Fulltext Introduction

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) are mesenchymal tumors that originate in interstitial Kajal cells (located in the intestinal wall) or their precursor cells [ 1]. GISTs are extremely rare and constitute only 1% of all primary gastrointestinal tumors [ 2]. Although GISTs may occur at any location within the gastrointestinal tract, the most common locations are the stomach (50-60%) and the intestines (20-30%) [ 3]. One third of all stromal tumors are located in the duodenum [ 4]. Although most of these are asymptomatic, some are accompanied by abdominal pain (50-70%), gastrointestinal bleeding (20-50%) or abdominal mass [ 1]. Surgical resection is the primary treatment option for nonmetastatic cases. Because submucosal invasion and lymph node metastases are uncommon, surgical resection without lymph node dissection is the most suitable surgical treatment [ 5]. Some authors maintain that pancreatico-duodenectomy is the best treatment option for stromal tumors, whereas others believe that a limited resection is sufficient because this treatment is associated with lower morbidity and mortality rates [ 5].

Case Report

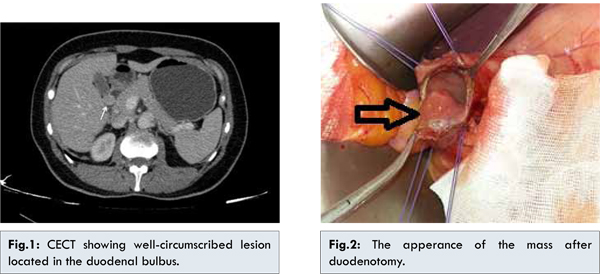

A 42-year-old female was admitted to the emergency department with symptoms of nausea, vertigo, and dark-colored feces, which lasted for one week. Her arterial blood pressure was 100/60 mmHg, and her heart rate was 110 bpm. She was experiencing tenderness in the epigastric region, and 300 cc of blood was aspired with nasogastric decompression. During endoscopic examination, an approximately 1.5 cm submucosal lesion was observed in the posterior region of the bulbus. Abdominal tomography showed a well-circumscribed lesion, including intraluminal and extraluminal components with a size of 18×15 mm located in the duodenal bulbus [Fig.1]. Following preoperative preparation, the patient was taken in for surgery. The aforementioned lesion was observed in the second part of the duodenum which was removed with negative margins [Fig.2]. There were no other pathological findings during surgical exploration. Following resection, the duodenal space was closed with primary sutures. Pathological examination revealed a gastrointestinal tumor with a low mitosis rate. The patient was discharged six days after surgery with no complications.

Discussion

Gastrointestinal tumors (GISTs) are the most common mesenchymal tumors of the gastrointestinal tract, and have previously been classified as being either leiomyoma (benign) or leiomyosarcoma (malignant) [ 5]. GISTs were first defined by Mazur et al. (1983), after they examined a smooth muscle tumor using an electron microscope and observed no neural or muscular activity [ 3].

Although the exact prevalence of GISTs is still unknown, it is assumed that incidence of the tumors is approximately 10 per million per year. Very small GISTs have been observed during autopsies of individuals aged over 50 years. This indicates that these tumors are slow growing [ 6]. GISTs can occur at any age and in any part of the gastrointestinal tract. Mean age of diagnosis is 60 years, and they are rarely seen in the elderly or children. The most common locations of GISTs are the stomach (50-60%) and intestines (20-30%) [ 3]. One third of all stromal tumors are located in the duodenum [ 7].

Most GISTs located in the duodenum are <5 cm. Tumors <2 cm are asymptomatic and are usually diagnosed incidentally while evaluating other medical conditions with tomography, endoscopy or surgery. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors may be submucosal, intramuscular, or subserosal. Ulcerations leading to bleeding may occasionally arise on the surface of the tumor. Tumors may grow toward the intestinal lumen or may show an exophitic growth pattern. Tumor size varies from 0.8 to 23 cm (mean 6–7 cm) [ 8].

There is no standard imaging method for diagnosing GISTs, and the only reliable method is biopsy of suspicious tissue; however, this is not advised for resectable tumors as interruption of the capsule of the tumor may lead to tumoral seeding to the surrounding zones. Therefore, preoperative biopsy should be considered for unresectable or high risk surgeries, to provide neoadjuvant therapy.One of the most important malignancy criteria for GISTs is mitosis count. However, preoperative needle biopsies do not give perfectly accurate results; therefore, mitosis rate cannot be used as a prognostic criterion [ 9]. Theoretically, any GIST has the potential to become malignant. It would be more accurate to classify these tumors as very low, low, intermediate, or high risk tumors rather than benign or malign. Furthermore, tumors <2 cm are considered to be benign. The most common criteria used to investigate risk of malignancy are tumor size and mitosis rate. For our patient, the tumor diameter was 1.5 cm and mitosis rate was <1 under 50X magnification zone; therefore, the tumor was considered to be low risk.

Fletcher et al. classified GISTs according to their tumor size and mitosis count (Table 1) [ 10]. In contrast, Miettinen and Lasota suggested that tumor location is an equally important factor for prognosis, and that tumors located in the stomach have a worse prognosis (Table 2) [ 11]. Two other factors that increase risk of recurrence are the existence of metastases and perforation of the tumor [ 11].

Surgical resection should be the preferred treatment for GISTs. Surgical procedures are well-defined for tumors located in the stomach and intestines [ 12]. However, there is no certain consensus on treatment of tumors located in the duodenum. There are different opinions about the respective benefits of pancreatico-duodenectomy and wedge resection [ 13].

There are three conditions under which preoperative medical treatment should be considered over surgery: (i) Tumors which are not suitable for total excision because of local invasion or metastases, (ii) Patients who are at risk for surgery, and (iii) If surgery is associated with high morbidity or mortality rates for patients. The three main aims of surgery are achieving a negative surgical margin, prevention of tumoral perforation and achieving a total R0 resection. Although GISTs are large tumors, they could easily be resected with negative tumor-free margins because of their noninvasive nature [ 14]. Because of this, a simple resection is sufficient treatment for tumors located in the stomach or intestines.

There is still no consensus on the optimal treatment method for duodenal stromal tumors. Similar survival rates have been reported for patients treated with pancreatico-duodenectomy and simple resection [ 13]. Therefore, simple resection with negative margins should be the preferred treatment, when possible [ 15]. Moreover, there is further discussion about treatment of cases with signs of positive microscopic residual tumor after resection. Re-resection, medical treatment or follow-up without treatment are considered to be the options. As lymph node metastases are rare for GISTs, usually lymph node dissection is unnecessary, unlike for intestinal adenocarcinomas [ 14]. Furthermore, special attention should be paid to protect the integrity of the tumor, as tumor perforation is a poor prognostic factor.

Exploration in our case revealed palpable mass had no relations with the vital organs that were close to the duodenum. The mass was excised with clear margins and no lymphadenectomy was required. It is our opinion that the excision with clear margins that was performed on the patient who has lower malignant potential due to the low mytosis rate and small size of the tumor was up to date.

In cases where surgery is not possible due to a known medical condition, imatinib is the drug of choice for neoadjuvant therapy [ 16]. Some studies have reported that, in cases of unresectable infiltrative tumors treated with imatinib, pathological response was 86% and the ratio of complete resection was 89% [ 17]. In addition to these benefits, other studies demonstrate that postoperative treatment with imatinib decreases recurrence rates [ 18]. Therefore, large infiltrative tumors should be re-evaluated for surgical removal after neoadjuvant therapy [ 19]. Further questions have arisen about when surgical treatment should be planned after neoadjuvant treatment. Many authors report that 6 to 12 months is the most suitable period for surgery. As resistance to drug therapy develops after 2 years, surgical evaluation must be done before 2 years [ 20].

Recurrences are usually seen in the peritoneum, liver or both. Peritonectomy and intraperitoneal chemotherapy might be preferred under these conditions [ 20]. Liver metastases must be removed if possible. However, diffuse peritoneal implants and liver metastases usually prevent surgical intervention. Therefore, other treatment modalities, such as hepatic artery embolization, chemoembolization, or radiofrequency ablation, should be kept in mind.

Conclusion

GISTs are infrequently located in the duodenum and usually present with bleeding. To achieve lower morbidity and mortality rates, partial resection should be selected over pancreatico-duodenectomy for nonmetastatic duodenal stromal tumors.

References

- Sturgeon C, Cheifec G, Espat NJ. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a spectrum of disease. Surgical Oncology. 2003;12:21-26.

- Duffaud F, Blay JY. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: biology and treatment. Oncology. 2003;65:187-197.

- Deitos AP. The reapraisal of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: from stout to the KIT revolution. Virchows Arch. 2003;442:421-428.

- Yao KA, Talamati MS, Langella RL, Schindler NM, Rao S, Small W Jr, Johel RJ. Primary gastrointestinal sarcomas: analysis of prognostic factors and result of surgical management. Surgery. 2000;128:604-612.

- Connolly EM, Gaffney E, Reynolds JV. Gastrointestinal stromal tumours. Br J Surg. 2003;90:1178–1186.

- Agaimy A, Wunsch PH, Hofstaedter F, Blaszyk H, Rummele P, Gaumann A. Minute gastric sclerosing stromal tumors (GIST tumorlets) are common in adults and frequently show c-KIT mutations. Am J SurgPathol. 2007;31:113-120.

- Miettinen M, Sarlomo-Rikala M, Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: recent advances in understanding of their biology. Hum Pathol. 1999;30:1213–1220.

- Miettinen M, Kopczynski J, Makhlouf HR, Sarlomo-Rikala M, Gyorffy H, Burke A, et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors, intramural leiomyomas, and leiomyosarcomas in the duodenum: a clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetic study of 167 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:625–641.

- Bucher P, Villiger P, Egger JF, Buhler LH, Morel P. Management of gastrointestinal stromal tumours: from diagnosis to treatment. Swiss Med Wkly 2004;134:145-153.

- Fletcher CDM, Berman JJ, Corless C, Gorstein F, Lasota J, Longley BJ, et al. Diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a consensus approach. Human Pathology. 2002;33:459-465.

- Miettinen M, Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors-definition, clinical, histological, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetic features and differential diagnosis. Virchows Arc. 2001;438:1-12.

- DeMatteo RP, Lewis JJ, Leung D, Mudan SS, Woodruff JM, Brennan MF. Two hundred gastrointestinal stromal tumors: recurrence patterns and prognostic factors for survival. Ann Surg. 2000;231:51–58.

- Tien YW, Lee CY, Huang CC, Hu RH, Lee PH. Surgery for gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the duodenum. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:109–114.

- Crosby JA, Catton CN, Davis A, Couture J, O’Sullivan B, Kandel R, et al. Malignant gastrointestinal stromal tumours of the small intestine: a review of 50 cases from a prospective database. Ann Surg Oncol. 2001;8:50-59.

- Sakamoto Y, Yamamoto J, Takahashi H, et al. Segmental resection of the third portion of the duodenum for a gastrointestinal stromal tumor: a case report. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2003;33:364-366.

- Jens Hoeppner, Birte Kulemann, Goran Marjanovic, Peter Bronsert, Ulrich Theodor Hopt. Limited resection for duodenal gastrointestinal stromal tumors: Surgical management and clinical outcome World J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;5:16–21.

- Goh BK, Chow PK, Chuah KL, Yap WM, Wong WK. Pathologic, radiologic and PET scan response of gastrointestinal stromal tumors after neoadjuvant treatment with imatinib mesylate. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2006;32:961–963

- Eisenberg BL, Smith KD. Adjuvant and neoadjuvant therapy for primary GIST. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2011;67:S3–S8.

- Neuhaus SJ, Clark MA, Hayes AJ, Thomas JM, Judson I. Surgery for gastrointestinal stromal tumour in the post-imatinib era. ANZ J Surg. 2005;75:165-172.

- Dematteo RP, Heinrich MC, El-Rifai WM, Demetri G. Clinical management of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: before and after STI-571. Hum Pathol 2002;33:466-477.

|